Ongoing Fiction (and a full published tale) by season…

Spring

Check back here for the release date of the first book in Craig’s upcoming Touch series!

With only a touch, Michael Calrissi can read your thoughts. His psychic skills, however, are a double-edged sword: an effective tool for tracking down serial killers, but an obstacle for keeping friends or lovers.

In “The Spider Bite Murders,” he investigates a string of disappearances in a remote California forest. Soon, Calrissi psychically pries into the secrets of both his detective partner and a would-be girlfriend, alienating both. His skill also reveals that something—or someone—is living in the oaky canyons, using deadly spiders as a weapon. Can Calrissi channel his abilities and crack the ghoulish case, rebuild the bridges he’s torched, and save the lives of the two people closest to him?

Summer

(Coming-of-Age YA from a boy’s perspective - READERS: COMING SOON - AGENTS: PLEASE INQUIRE)

Tommy, 17, has to figure out Elaine, his “perfect” girlfriend, and her mind-blowing past. Then he realizes his best friend’s somehow morphed into a methhead and is about to go off the rails. Just to pile on, Tommy’s always tried hard not to think about his dead mom and what happened when she died— but suddenly more memories of her flash back each day…

The clock’s ticking. It’s spring now, but he’s only got until summer to deal —with all of it.

Falling Off the Mountain

Excerpt

Midnight. Snow whispered against the panes, and Dad snored from down the hall. I was wide awake, Elaine’s words looping in my mind: “Tommy, I’m leaving in three months...”

She’d called after dinner. Her voice was low, almost a whisper. Neither of us can afford a cell, and their phone was corded. So, zero privacy. I pictured her mother, hovering there like a vulture.

“Leaving?” It came out like a foreign word. My brain felt fuzzy and slow.

“Mom’s moving me the day after graduation.”

“Like, to another cabin in Pine Knot?”

“No, Tommy. Listen. She's moving me out of California…”

Fall

Siblings Daniel and Sarah discover an elderly woman who looks young...and a grown man who’s actually a kid. They trace these unwanted transformations to the sinister Timemaster—but when they confront him, they pay. He changes Sarah, 12, into an elderly woman who is put in a locked convalescent hospital. He turns Daniel, 11, into a pre-speech infant. He’s taken in by a foster mom.

No one believes Sarah, and Daniel can’t talk. It will take every ounce of their ingenuity and weak psychic skill to even get together again. Then, as an old lady and a baby, the pair must rally their enemy’s seven other victims against him—before they all run out of time.

Seven Clocks

(Speculative-Supernatural-Adventure for Middle Readers - READERS: COMING SOON - AGENTS: PLEASE INQUIRE)

Excerpt

…I frowned. “If you don’t like your beard, why not shave it off?”

“With a razor? Nah-aw. Razors are sharp.” He set the Bubble Magic on the floor. He didn’t bother to screw the lid back on. Then he picked up a toy car.

“Mr. Powell—” Daniel started.

“I’m Chuck, ’member?” he said in a hurt voice. And then this full-grown man started running the red car up and down his thigh, guiding the tiny vehicle through wrinkles in his pants leg. In back of his throat he made the sound of an auto engine.

“That’s right, Chuck. You told us that.” Daniel spoke in a super gentle voice. “Chuck, is this your trailer?”

“No. This old man, Mister Feinstein, saw me crying under one of his apple trees. I said I got no place to go, and he felt bad for me, so he lets me live here. He gives me some money, too. That’s how I buy my candy.”

I had a killer idea. “I like that toy car,” I said. “Do the doors open?” I reached over and touched the side of the little auto—and I also touched Mr. Powell’s hand.

And—yes!—I figured it out. Don’t know why, but my hunching was working, for once.

“Doors don’t open on that car,” he said. “But the front wheels turn. Lemme show—”

“Chuck, how old are you?” I interrupted.

“Six,” he said automatically. He slowly lowered the car, biting his lower lip, and stared at us to see if we’d heard. “I mean...twenty-six. I’m twenty-six.”

Winter

A Letter for the Bayou

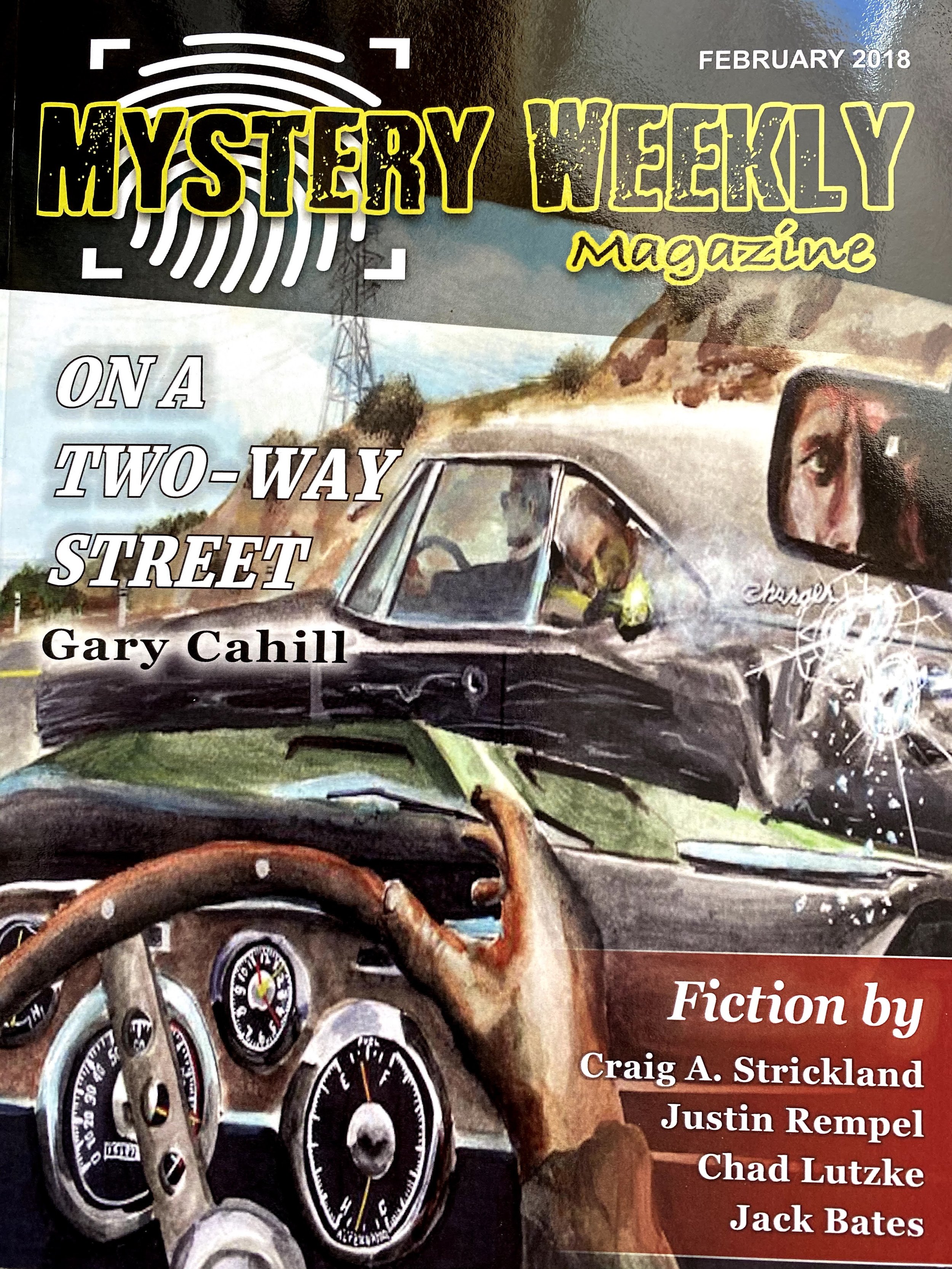

In 2018, MYSTERY WEEKLY MAGAZINE published my mystery story “A Letter for the Bayou.” The magazine teased the story as a poignant tale of an old detective hoping to spend his retirement with poetry and a quiet life. But when the peace of the Southern bayou in his backyard is violently shattered, suddenly he finds himself back on duty.

“Green shadows she prowls.”

The line was not meant to describe anything literal. Yet I’d barely written it before my neighbor girl stole, as if cued, into her overgrown backyard. She passed stunted pines and wildflowers and headed toward the canyon rim of Turtle Bayou. Two fingers held aloft the hem of her dress; in the other hand she carried a sheet of paper.

Melodica, I recalled, was her strange name.

I set aside my poem-in-progress and stilled the rocking of my chair. The child was about seven, blonde, her skin a translucent white. This was the first time I’d seen her in daylight.

The ethereal creature paused at the chasm-edge, a spot of pale against a riot of greenery. Realizing her peril, I stood to shout, but she raised the paper so theatrically that my warning cry died in my throat. To interrupt would have been akin to yelling during a tender moment in a play.

She released the paper, sending it toward the bayou, far below. For seconds her hand remained out, fingers splayed as if waving farewell. The page sawed itself to and fro, descending to the ends of the vines which wept from the canyon rim, then disappeared into the verdant darkness—no doubt to join the mats of water lilies floating at the bottom.

I could not help but be charmed by the romance of mailing a letter into thin air. But was it a game, another symptom of the girl’s eccentricity, or—something else?

She turned and walked back. Her shoulders seemed slumped with the weight of grief. There was a mystery here. I had avoided mysteries for years, but this one, shoved under

my nose, rekindled my curiosity. If the dropped page constituted a letter, what words did it contain, and to whom was it sent?

I rose, sprayed on mosquito repellent, and took a stroll.

I am in my early eighties, twenty years into retirement, and a good fifty past my prime. Old men, I’ve discovered, can still do marvelous things; they just need more time. Thus did I successfully reach the canyon bottom—using a steep, rough footpath cut in cruel switchbacks—though what would once have taken three minutes now took a full ten.

The fertility of the Southern soil has reduced this trail to a thin line. All else is a blanket of green springing from brown layers of decay: swamp grass, spiny-tipped palmettos and rushes. Overhead, cypress and crouching live oaks droop into the black water itself. The dank perfume of blooming flowers and rot intermingle, rising into my nostrils like a physical slap. The smell of the bayou. Setting for my poetry; inspiration for my idle years. And balm for a troubled mind.

Access to this place was the reason I chose this house among all others in which to retire.

The paper lay unfolded and partially submerged in the middle of the water, the letters printed in large, childish script. From the shore, I could only pick out bits and pieces: “When will you come...” and the single words “play” and “miss.” Holding overhead branches, I carefully leaned out, but the sluggish top current carried the cryptic message from reach even as I watched.

I marked the direction it was bound. Beyond the maze of water-lilies, a beard of Spanish Moss hanging from a water-bound cypress caressed the surface, acting as a screen. The strands were decorated with waterlogged scraps of paper.

It looked like Melodica had sent other letters—but why?

I looked about, sweating in the steamy atmosphere. In spite of the repellent, mosquitoes whined at my ears. Then, in a narrow band of black mud marking the border of earth and water, I spotted two boot prints. The toe-impressions faced the water. A clue?

I smiled to myself. Old man trying to play detective again. Reliving his youth.

The prints were unusually large and recently-made. In one lay the impression of an anchor. Being an occasional angler myself, I recognized the brand as a high-quality maker of men’s fishing boots.

I daydreamed my way back up the hill, trying to put the various facts together—or at least find the poem which lurked behind this. At home, I plunked ice cubes into a glass of sun tea and sat again in my rocker. The sticky breeze caressed my face.

I turned over the few things I knew about the girl and her family.

Her stepfather, George La Forte, was a middle-aged antiques dealer, a confirmed bachelor. Five years back he suddenly brought a young wife—complete with toddler daughter—into his family home. They were my closest neighbors; the next nearest houses stood a quarter mile away. The La Fortes and I maintained a passing acquaintance of smiles and nods. I had spoken to neither Melodica nor the wife, Lydia.

Both mother and daughter were classically beautiful Southern belles. Chance observations, however, had been initially jolting. On moonlit nights I saw them in the backyard, dancing to unheard music, each with unseen partners. In time I became blasé about it. Perhaps they were feeble-minded; perhaps they were free spirits. Who could say? They seemed otherwise functional. Melodica attended the local school, and Lydia, from what I could observe, maintained a household, though she did not drive.

I sipped my tea and pondered my clipboard. I wouldn’t be mulling over such gossip if my current poem hadn’t been giving me fits. I’d been trying to commit to verse the notion of a woman, finding romance in a chance meeting at a bayou. So far I had:

Green shadows she prowls

the riddle within:

loneliness.

Without, the mist breathes

Frogs sing

the dark wet heart of summer

throbs

She yearns for the swamp

and the answer:

love.

How to go from here? My mind wandered again. The only real concern, I decided, was for the welfare of Melodica. Her parents needed to know she’d been playing dangerously close to the cliff. I had to tell them I’d seen her there.

That night I baked a loaf of sourdough and took it to the white-columned La Forte mansion. Elaborate stained glass decorated the front door, guarded by twin lions of stone. George’s haggard face appeared five minutes after my knock, mustache carefully clipped, gray eyes brooding. He seemed not to recognize me; then his lips crumpled in a failed smile.

“Evening,” he said. But he looked betrayed. Probably wondering why, after all these years, I’d chosen to break our unspoken agreement for mutual privacy.

“Perhaps I’ve picked a bad time. I just wanted to bring you fresh bread.”

“Come in,” he said. He took the foil-wrapped loaf, and silently led the way.

It was my first peek inside. Their home was walled with gilded mirrors, reflecting beautifully-preserved furniture from the 1700s and 1800s. In an alcove clustered a mass of ancient human faces, each with a frightful expression and a fringe of leaves. From my readings I recognized this as a collection of Gothic green men, thought to bring good fortune to gardens.

I followed him into a chamber in which dark, burnished wood dominated. Trout were mounted on lighter-colored wood, alternating with a series of fine old paintings. All of the latter pictured ponds with pads of waterlilies. I intuited that these feminine works had been his wife’s idea, perhaps to counterbalance the masculine trophy fish. In the room’s center, an oak pedestal held a crystal bowl. Inside, a dead water lily floated, its wilted petals spread like an open hand.

This was the sitting room, but we did not sit. “Lydia left again,” my host blurted.

“Oh? How long will she be gone?”

He shrugged, pausing to wipe perspiration from his forehead with a fierce swipe of his sleeve. “Jesus. Maybe forever, for all I know. She tends towards odd behavior, and fits of depression as well.” His steel-colored eyes met mine as if seeking understanding; he knew I would’ve witnessed Lydia’s midnight ballets. “No note, no warning, just up and takes off sometimes. Of course, we’d had an argument...”

“Where did she go?” I asked, surprised at this turn in events.

He shrugged. “She’s usually picked up by Zora. Her sister. From ‘Orleans.” “I lived in New Orleans for a spell. Knew a Zora there,” I mused gently, though I had in fact never known a “Zora” in my life. Some part of me was instinctively gathering information, tapping skills dormant for twenty years. I wondered at myself even as I gave life to my next lie: “Alexander. Zora Alexander. Same woman, by any chance?”

“No. Zora Rydeckee. Look, John, so good of you to bring this bread, but I’m afraid...”

“I understand.” I stood and turned, only to see Melodica hovering between sitting room and hall, pale face reflected again and again in the mirrors. She seemed a tiny white statue of mourning, sadness incarnate, I thought, in the depths of my poet’s soul. Meanwhile, the cop part of me noted her modest swimsuit—though they had no pool and it had been dark for hours.

“Melodica,” said my host. “Come here.”

But she was already gone.

“Melodica!” This time he yelled, veins standing out on neck and temples.

Nothing. And no one. It was as if she had never been there.

“Honest to God. Been her stepfather five years, yet she mostly ignores me. I love both dearly, but can’t communicate with either. She and her mother are of the same strange mold.” He looked up, distracted. “It’s odd Lydia didn’t bring Melodica to ‘Orleans. She usually does.”

I was hesitant to interrupt his reverie. “George,” I said at last. “I saw Melodica alone out in back this afternoon. It worried me. She was terribly near the dropoff.”

“What?” He stared at me. “Where?”

“Near the path. Staring down at the bayou.” For some unnamable reason, I didn’t want to tell of the letter. “At about five o’clock.”

“I’ll talk to her,” he said. His face reddened, and the frustration written there frightened me. I took him in from head to toe. Strong, deadly serious—and with unusually large feet.

“Good night, George,” I said. He nodded and shook my hand mechanically. I walked out, unescorted, past polished Louis XVI chairs and the cold leering faces of green men. I couldn’t help but wonder whether my neighbor’s manner spoke of intense love—or a capacity for violence. If it was the latter, then I’d possibly helped light a sort of fuse.

Sure enough, I was awakened at two a.m. by a small verbal explosion. “Where?” yelled George La Forte, words measured and terrible in the sultry night. “Where were you going?” The voice cut off, as if he’d moved inside from out. I strained to catch the high notes of a child answering him, but I could not hear them. Neither did I hear La Forte again.

I lay in bed, wide awake, fluffing and refluffing an already-plump pillow. A city man, used to shouted domestic squabble echoing in apartment courtyards, would have turned over and slept. But I am a country man, accustomed only to a chorus of crickets and bullfrogs. Questions tormented me. Was Melodica okay? It sounded as if he’d caught her leaving the house in the night—if so, where had the child been going? Or was Melodica even the target of his tirade?

I knew only one thing for certain: sleep was out of the question.

An hour after the outburst, I heard movement outside. It might have been raccoons—entire families of them troop through here—or a burst of wind, parting the hair of the wild grasses. But it could also have been a person, slipping down the steep path to Turtle Bayou.

Just before daybreak, La Forte’s car screeched down the street. He had not returned by 8:30. I watched the yellow school bus, its side imprinted with the legend “Brigham County School District,” pull up to the curb, honk, wait a few minutes, and rumble off without Melodica.

The sight wrenched me.

So she hadn’t gone to school. Maybe her mother and aunt had come for her in the wee hours. That would, perhaps, explain the yelling. It was none of my business either way, but I needed to know everything was all right.

Without hesitation, a yarn spun its way into my head. New Orleans information had only one Zora Rydeckee. She picked up the phone on the second ring.

“Yeah?”

“My name is Robert Hagstrom. I’m a truant officer for Brigham County.”

Silence on the other end.

“A student, Melodica La Forte, didn’t show for class this morning. Her stepfather said the mother and girl sometime stay with you. I just wanted to verify that...”

“Yeah, they stay now and then. Gives ‘em a break from old Georgie. He’s never understood ‘em.” I felt relieved, until she went on. “But they weren’t here last night. Haven’t seen Lydia or Melodica in two months now. Are they missing, ‘zat what you’re telling me?”

“Don’t know, ma’am. This is just a routine call.” I thanked her and hung up.

The problem? I was out of routine explanations. Only other place to look was the bayou.

I strolled out into my garage and took up a long aluminum pole with a blunt hook, the kind people keep around swimming pools. I have no pool; I use the pole to swipe magnolia leaves out of the rain gutters. Today I needed it to try fishing up that child’s letter, and to get at the remnants of the other letters—the only remaining clues I had.

I fingered the cold aluminum. Of course, I’d swish it around a bit as well, just to check that there wasn’t anything else under that black water. After all, it was possible—wasn’t it?—that George La Forte murdered his wife, and, donning fishing boots, dumped her in the bayou. And was it too farfetched to imagine that Melodica knew she was there and, being odd and fanciful and unable to comprehend death, was trying to contact her mother by sending letters?

I hurried down the path, unnerved. My foot slipped once, but I kept my balance, narrowly avoiding a tumble. Pine needles jabbed through my clothing. By the time I reached bottom, my heart was throbbing so badly that I had to stop and pop a nitroglycerin tablet under my tongue.

I took a deep breath and looked around, trying to lower my runaway pulse. The scene was much the same as yesterday, but my attitude towards it had darkened. The hanging Spanish mosses, the gnarled oaks, even the nodding multicolored heads of the wild orchids now seemed invested with malevolent potential. Even the crickets sounded ominous. My poet’s imagination considered a rubber tree towering overhead, transforming its silhouetted branches and pointed horns into hands clutching daggers.

I rallied myself and marched toward the water. In my zeal I blundered on the narrow mud-patch containing the bootprints. I almost stepped on them—an unpardonable crime-scene stupidity. I looked at the prints side by side, and was struck by how much deeper my sneaker tracks looked than those made by the fishing boots. La Forte’s feet were larger, but he seemed roughly the same weight and height as me. Why wouldn’t they be of similar depth?

Ahead, a distorted oak extended over the water, the trunk nearly horizontal at the base. It seemed the best approach. With some difficulty, I mounted the tree like a man on a horse and scooted out several feet. Mosquitoes settled on my arms and face and began to feed. I ignored them and extended the pole.

I no longer cared about the letters, pasted on the Spanish moss. I splashed the aluminum implement into the water near the boot prints and stirred like a witch at her cauldron. The sweet-rot stench of swamp water rose in the air. I stared down, hoping I would encounter no resistance.

But something was there.

A log, perhaps? A dead water-bird? I prodded deeper, trying to get under the submerged thing.

A hand suddenly surfaced from under the bayou. A small hand.

I groaned.

I shifted the pole a bit and one side of Melodica’s drowned face floated under me like that of a porcelain doll. She was wearing the little swimsuit I’d seen last night.

La Forte must have carried her right past my bedroom. Had she already been dead? Had he killed her following the screaming I’d heard?

I felt ill, yet I forced my hands to keep in motion. I continued probing with the pole further out, among the lattice-work of water lilies: hundreds of white flowers, each abob on its own raft of green. Soon I located Lydia. At my prodding she, too, rose from the bayou, face down at first, then rolling with luxurious deliberation, head haloed with skittering waterbugs. She was still lovely, though the swamp had been at her several days—liquefying the first layer of skin and darkening her hair. Making her its own.

My hands weakened. I dropped the pole. It landed with a splash, rocking the corpses. Mother and daughter moved together then stopped, suspended, tangled in the lilies a few feet apart, kept afloat not by love but by the gases of their own decomposition.

I hugged the tree. The sight of murder victims now, after all this time, was a dirty revelation. The human spirit can only witness so much killing. Since retirement I’d tried to purge myself. I’d not kept in touch with fellow homicide dicks, nor picked up one paperback murder mystery. I skipped over newspaper stories promising violence. Instead, I holed myself away and penned flowery romantic poems by the score. Avoidance. Denial. I’d invested much in those words. Now all was crushed by this pathetic sight not 100 yards from my very backyard.

A wild turkey’s cry shrilled out, echoing up and down the bayou.

I uncapped the bottle and popped more nitro. This is what came of not knowing my own three neighbors. Against expectation, George had turned out to be the crazy one. I couldn’t see enough of their bodies to determine cause...had they been drowned? Strangled? Poisoned?

A footstep crunched on pine needles. George La Forte stood in the path 50 feet off, cradling a shotgun in his arms. A Lanber, from the look; I recognized the Western-style metal plate just above the butt. The barrel gleamed, copper-colored in the yellow swamp light. He stared wildly at the bodies, then walked toward me.

I struggled off the trunk and stood, back to the twisted oak. I was unarmed, and the lush, interwoven vegetation gave me nowhere to run, but it felt infinitely better to face him on my feet.

He drew close, his sorrowful eyes riveted on the bayou. Shadows crisscrossed, cleared, darkened and crisscrossed again on his face, making him resemble nothing so much as one of his own bestial green men. “How’d you figure it out?” he asked, stopping not fifteen feet away. It would be well within range for a hunting shotgun like the Lanber.

The crickets, I noticed, had stopped their chorus.

“Happened to see your stepdaughter sending letters over the cliff.” I muttered. The knobby bark of the oak pressed into my back.

“Is that what she was doing?”

He hadn’t pointed the Lanber at me, not once. He carried it muzzle-up, holding it possessively, purposefully.

Like a hungry man anticipating a bite.

Again I revised theories. The gun was not for me. George La Forte had come to Turtle Bayou to blow his brains out.

I cleared my throat. “It took me until an hour ago to guess who Melodica was writing to.”

“She told me her Mama was swimmin’ down here.” He crouched. Closed teary eyes. The shotgun’s barrel nuzzled his cheek. “I dismissed it, ‘cause neither could swim.”

“You told me Lydia was at her sister’s,” I prompted.

“That’s what I thought. Zora took her in, if we had words. When Melodica wasn’t in bed this morn, I drove to ‘Orleans, thinking she’d picked her up in the night.” He choked back a sob. “Pieced it together on my way back. Knew this was what I’d find.”

“Why the gun, George?” I asked.

“Lydia killed herself. Threw herself in the water because I couldn’t make her happy. Then Melodica drowned going after. It’s on me, John. All on me.” He held the gun so tightly his knuckles were bone-white.

I saw it clearly: George would fall in a spray of red, ducks and geese and the other swamp birds would rise like screeching angels, the corpses of all three neighbors would lie at my feet, and I would hear the booming echo of that shotgun filling the bayou, my peaceful, verse-inspiring bayou, every day for the short remainder of my life.

I cleared my throbbing head. This was not a murder case. A man still lived, and I had a chance to save him. It had been years since I’d tried to talk down a suicide. Could I manage? Maybe. If I could I offer grief instead of guilt.

“Lydia didn’t kill herself,” I blurted. “These were accidental drownings, George.”

He shook his head. “Bullshit. We argued, she was fragile, couldn’t take it.” He moved the gun’s muzzle under his jaw. “Sorry you had to be here, John...”

An idea clicked. Something I saw at their house last night…

“I don’t think she was mad at you at all, George,” I said. “Let’s find out why she really came down.” I waded noisily into the water, praying that the mud wasn’t too deep. No time to fetch my pole, which had drifted off toward the middle. I had to get his attention, now.

I moved toward Lydia, the fetid smell of disturbed swamp water rising around me.

“What are you doing?” His voice filled the bayou.

“George, drop your gun and watch.”

I warmed to my hunch. But George needed convincing, and only a little luck would deliver proof. I plodded through the thick, warm swamp-bottom, water past my waist. The clinging mud hindered my balance and sucked at my shoes like a thing alive. A person could easily drown here, I thought. Lydia floated before me, her daughter alongside, both at peace in the ebony water. The words of my nascent poem rewrote themselves in my head :

In green shadows they died

one seeking love

the other

...simple beauty

Was it possible? There was a watch on her right arm, so I moved her about to reach her left hand. As she circled, and the water bugs danced, her booted feet brushed my thigh. So—she had put on her husband’s fishing boots before coming down. If suicide had been her intention, would she have cared about dry feet? Perhaps that was something to tell George, just in case her hand was empty.

I glanced back. He was watching, but the shotgun still propped up his head.

Let her hand not be empty, I prayed.

I seized her wrist. It was cold as bone, but I held it, dripping, out of the water. Her fingers clutched something white and folded. “Look,” I wheezed. “A water lily, George.” He stared, dumbfounded. I dropped the arm with a splash, and supported myself by leaning on the roots of a huge cypress reaching out over the water.

“She loved the lilies, didn’t she?” I panted. “I saw the paintings. She came down to pick a flower. That’s all. For the bowl in your sitting room, maybe. And she slipped.”

The gun fell to the mud. He covered his face. Sobbed. The crickets resumed creaking. I clung to the roots and popped my last nitro pill. Then I waded slowly toward George, arms pinwheeling to stay upright. I didn’t know what else I’d say to him, nor he to me.

I only knew we were going to have to help each other up the hill.

THE END